Kabuki Theatre in Japan

#1 Introduction

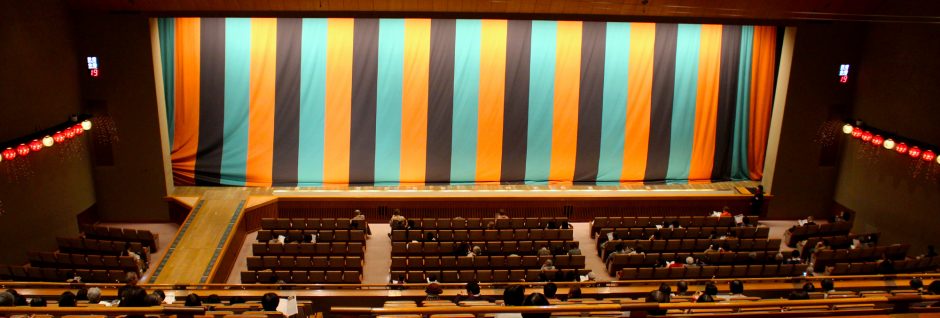

Kabuki is one of the traditional Japanese form of theatre. It is commonly seen as the theatre with all the elaborate and flamboyant makeup and fancy costumes, but in reality it is far more interesting and deep than that. On January 24th I got to see a play at the Japanese National Theatre in Tokyo as part of an AFS trip, and have since read up quite a lot about the art form that is Kabuki, including The Kabuki Handbook, written by Aubrey S. and Giovanna M. Halford. I would highly recommend you reading it if you are interested in Kabuki theatre, it really is quite an enjoyable read.

#2 History of Kabuki

I will begin the history of Kabuki with the history of the word itself. 歌舞伎, as it is written in Japanese characters, illustrates the meaning of Kabuki rather well. 歌 means sing, 舞 means dance, and the final character 伎 means skill. However that is not where the word originally comes from, as these Kanji were added afterwards to fit the sound, which is called Ateji. The real etymology is actually quite different. The word is believed to be derived from 傾く [Kabuku], which means to lean or to be out of the ordinary.

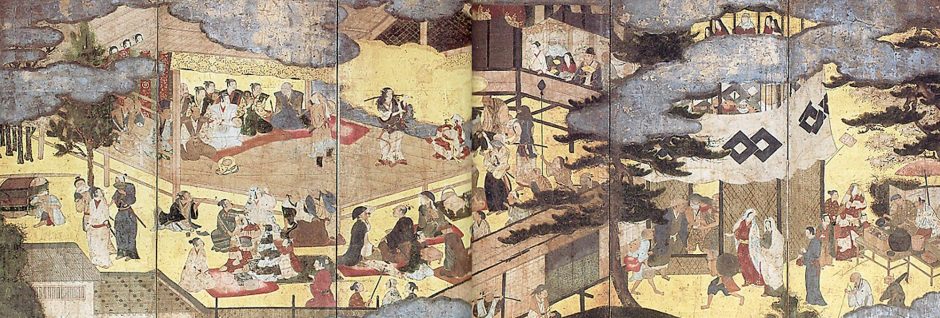

Okuni Kabuki-zu Byōbu, the oldest known portrait of Izumo no Okuni, Kyoto National Museum.

Early Days

The origin of Kabuki can be found in 1603. The Originator, Izumo no Okuni [出雲阿国], who was a shrine maiden at the Izumo shrine, was known for her skill in dancing and acting. She was known for her performance of the Nembutsu Odori, a type of dance, her adaptation being known for being full of sexual innuendos, and funny acting skits. She stopped her work at the shrine and became a performer.

In 1603 she gathered a troupe of social outcasts and prostitutes, whom she taught how to sing, dance and act, and they performed on the riverbed of the Kamo River, as well as at the Kitano Shrine. She became immensely popular, the audience labeling her performance as Kabuki because of it’s inherent oddness and eccentricity. Soon there were many copy-cat groups performing, and it became an art form. These troupes were all female, so women played the roles of men as well.

In 1629, women’s Kabuki was banned for being to erotic, along with its connection to prostitution. After the ban was established, young men took over all parts and started Onnagata, which will be further discussed in the acting styles section. As this was also connected to prostitution, by customers of both genders, it too was banned.

After a short decline in popularity, adult men started playing Kabuki, continuing the trend of playing both male and female characters. Here is when the themes started switching to more modern themes with more thought put into the content of the performance, and not just the visuals and song. It could be argued that Kabuki was the start of Japanese pop culture, which, in my opinion, is pretty darn cool. Because of the rowdiness of the crowd and the prostitution, Onnagata was banned entirely, along with young male roles as well, but this rescinded in 1652.

Golden Age

1673 to 1841 is seen as the golden age of the Kabuki theatre. The art form was established, with clear structure and technique. Many different forms of theatre that came to be during this era influenced Kabuki, and many of the most famous plays were either adapted from them or written especially for Kabuki. As the government at the time loved banning things, plays with lover’s double suicide were banned after they spawned real life imitations. Here is also when the Mie poses and the now standard dramatic makeup originate, both of which I will cover in later sections.

The next 30 years weren’t good ones in the Kabuki world. Due to extreme droughts in the 1840s several theatres burned down and the government at the time, seeing their chance to end the mixing of merchants, actors and prostitutes, and forbid the rebuilding of the theatres in the cities. This, along with strict regulations spurred the start of underground Kabuki, which kept changing locations to evade authorities. The abundance of extravagant costumes and makeup was lost by this.

Luckily, in 1868, the military government fell apart and the emperor was reinstated, Kabuki surged in popularity again. New styles came to be, and old plays were adapted for the modern audiences. The foreign influences helped make Kabuki what it is today. It became so popular, the emperor even sponsored some plays.

Modern Day

After WWII, the occupying forces – drum-roll please – banned Kabuki yet again, yet this ban was rescinded in 1947. Yet Kabuki wasn’t very popular at the time, as it was heavily connected to the past, yet this slowly changed after more modern adaptations were created and new innovations came about.

Nowadays, Kabuki is more popular than ever, with groups touring around the globe, and English earphone guides exist at most theatres in Japan to allow for a larger audience.

Kabuki was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2005.

#3 Acting Styles

Before I talk about the plays or the stage, or anything else really, I’d like to talk a bit about the different acting styles in Kabuki. As I mentioned in the history section, Kabuki is played exclusively by men, and there are 3 rough categories one can categorize their performances in; Onnagata, Wagoto and Aragoto.

Onnagata is when male actors play female roles, the Japanese word Onnagata [女形] literally meaning “female form”. Kabuki Onnagata requires extensive training and uses many different techniques to imitate and exaggerate female movement in a way that has become quite its own. All Kabuki actors are expected to be able to perform in the Onnagata style, which is far more than the mere cross-dressing it is seen as in much of the western world.

Wagoto is similar in style to Onnagata, and is when male actors play the roles of young men. It is a very feminine acting style full of fluid motions and beautiful costumes. Wagoto tends to uses all white makeup over the bold makeup of Aragoto.

Aragoto can be translated as rough style, characterized by bold movements and the famous Kumador; white, red and blue makeup. Big, padded costumes utilizing big, bold patterns. Aragoto is known for its grand style and scale, superman-like and bombastic. All movements are colossal and deliberate, and there is a whole array of made up words used simply for emphasis.

#4 Acting Techniques

Unlike western theatre, Kabuki isn’t trying to make things feel real, and it isn’t trying to get you lost in the story. Kabuki is fully aware that it is a performance, and is honing in on that as much as it can. Everything in the play is larger than life, all of the movements, all of the dialogue.

Mie is a technique that was developed in the golden age of Kabuki, and is one of the best parts about Aragoto plays. “Cutting a Mie” is when, at the climax of a scene, an actor performs a statuesque pose and freezes in it. Mies capture the tension and hold it for a few seconds, after which it is released and the play continues. A Mie is announced by the clapping the Tsuke, or wooden clappers [more on that later]. The leading Aragoto character may perform a Roppo exit, in which he cuts several Mie in rapid succession while walking down the Hanamichi. Lesser known actors might even turn their backs to put emphasis on the important moment.

Dance in Kabuki follows many strict rules, as do most aspects of Kabuki. The two categories most Kabuki dances can be put in are Monomane, which is when an actor portrays a certain character using gestures and poses, and Mitate, which is when a character uses a certain prop to symbolize another, for example a samurai dance-fighting with a fan instead of a sword. Mitate are incredibly complicated and require deep knowledge of the play, and there are countless subtleties to both of these forms that are hard to explain.

This is all rather difficult to explain, so here is an example:

#5 Costumes

Kabuki costumes are heavy. Beautiful, but very, very heavy. A single costume can weigh up to 20kg, try wearing that for a several hour long performance including dance elements, while still moving gracefully. There are many different layers and folds that have to be carefully adjusted every time an actor moves, which is what the stage assistants are for.

Kabuki costumes, especially in Aragoto, use bold, bright colours and patterns. Most of the costumes use real silver and gold threads, and are seriously expensive. Even though they cost so much and require special craftsmen and women to produce, they are often discarded after a single theatre run as the colour fades and they begin to smell rather unpleasantly due to sweat.

However, not all costumes in Kabuki are big and flashy. Especially Sewamono and Kize Wamono plays [17th – 19th Century] are a lot more toned down and represent the fashion at the time, with high emphasis put on historical accuracy. Jidaimono, plays in the classical style, utilize “modern dress”of the time. From Kimono to Hakama to Uchikake to many, many more types of traditional Japanese clothing.

Costume changes are very common, and are often done on stage. These are called Hikinuki, and are quite dramatic. Often, they are to reveal the fact that a character was disguised as another. Within seconds, costume and sometimes even makeup are changed, mostly with the help of personal stage assistants who hide behind the actor.

Extra care is put into dance performances, with special costumes and bright colours.

#6 Makeup | Wigs

Kumadori, the stylized makeup found in historic plays is one of the most recognizable aspects of Kabuki. Red is used to put emphasis on passion and virtue, while blue symbolizes things like fear and jealousy. Black is also seen as a “bad” colour. Main characters often have pure white makeup, as do ladies and young handsome men, which comes from ladies in Japan historically favouring white makeup as it allows for a wider colour palette in clothing. All actors do their own makeup, no matter how complicated.

Masks are often falsely associated with Kabuki, and are instead used in Noh plays, which I may write another post about some time.

Makeup is not used to enhance or accentuate existing traits, as is done in western theatre, but to obliterate the physical personality of the actor and reduce his facial expressions to the specific role. Emotions are associated through the colour of the makeup more than by the facial expression of the actor.

Wigs also play a big part in Kabuki, and are called Katsura. Each costume has its own type of wig associated with it, and the styles and weight range from simple and light to ornate and incredibly heavy. Specialized craftsmen and women produce these wigs from almost exclusively human hair. Most wigs are custom made for the actor, starting from a copper-sheet head mold on which the hair is layered and stylized.

#7 Stage Design

Hanamichi

On of the biggest differences between western and Kabuki theatre is the Hanamichi, or “flower-way”. The Hanamichi is a pathway on the left, which connects the stage to the back of the theatre. Important characters and groups often make their entrances and exits here, such as the Roppo exit I mentioned earlier. Izumo no Okuni, the founder of Kabuki, is said to have pioneered the Hanamichi. There are footlights on either side and a trapdoor called Suppon, located three-tenths of the way from the stage, on which entrances and exits can be made as well. This path is said to have been invented to achieve a higher dramatic effect, by bringing the actors closer to the audience. The most sought after seats in the Kabuki theatre are the ones closest to the Hanamichi.

Contraptions

The Kabuki stage is full of contraptions and machinery to create the best possible viewing experience. A good example of stage technique is Chunori, where an actor is suspended by ropes and “floats” over the stage or even the audience. In the play I saw this was combined with other practical special effects. Usually magical creatures such as ghosts, foxes and possessed humans utilize this contraption. Most stages have a dual revolving stage, which allows for quick set changes.

Curtains

There are several different types of curtains that can be drawn, with the main one, called Johiki-Maku, having green, terracotta and black stripes. Maku means both act and curtain in Japanese, which shows how close the two are connected, when the main curtain is drawn, the act is over, and when the final act is over, there are never any curtain calls, so be sure to applaud before then. There are many other types of curtains, such as pale blue ones to signify the sky, or black ones to symbolize night time. These are often used for introductory scenes.

Lighting

The lights are kept on during the entire performance so you can read the guide to catch up on what is happening [trust me, you’ll need it…], or eat a bento [the performance is several hours long, you’ll need a snack]. Don’t leave the room while a scene is playing though, you can get up and leave between scenes though.

The most standard set is the Niju-Butai, which is a raised platform in the center of the stage representing a house/camp/castle.

The Kabuki stage is very wide, yet not very deep.

#8 Birds, Beasts and Butterflies

I’d like to talk a bit about animals in Kabuki, or as the Kabuki Handbook by Aubrey S. and Giovanna M. Halford puts it nicely, Birds, Beasts and Butterflies.

As in most theatres, no real animals are used, but that doesn’t stop the shows from being full of spectacles. Just look at the Kabuki stage horse, a technique passed down for generations by a certain Kabuki family. There used to be quite an odd little tradition called hay money, where the actor had to give a tip to the two stage assistants operating the horse, or risk an unfortunate accident. The latter half of the tradition doesn’t exist anymore, the former however has remained.

Small beasts such as dogs or foxes are played by little boys in skins, and big beasts such as dragons, sea monsters and serpents are played similarly to the way they are in China, requiring quite a few people.

Birds, butterflies and other small flying creatures are manipulated by stage assistants using long rods [Sashigane]. The play I saw opened with many beautiful creatures flying through the stage, which really was very impressive.

#9 Clappers | Applause

Earlier I mentioned that clappers are used to announce the cutting of a Mie, but they are actually used for many other things as well. There are two different types of clappers, the Ki and the Tsuke.

The Ki are a lot bigger than the Tsuke and are used to mark the drawing of the curtain. They are struck backstage.

The Tsuke are the far more unique. A stage assistant, located stage left, strikes the Tsuke to call attention to important moments. These could be many different things, from a Mie, to an important line being spoken or a decisive action being taken. Tsuke are struck on a wooden board.

Moving to applause. Although nowadays clapping is common, a much older and more flattering way of showing ones appreciation is by shouting the actors name and number, or Yago. Yago literally means “house name”, and is the name passed down

#10 Music

There are many different types of music used in Kabuki, yet they all fall into two broad categories, Geza and Shosa-ongaku. Almost all music in Kabuki is played live.

Geza includes music and sound effects that are played to enhance the scene, yet the musicians are not visible to the audience. Usually, they sit behind a black bamboo curtain called Kuromisu.

Shosa-ongaku is played on stage, and directly connects to what is happening, it might be narration during Monogatori, or it might be a band accompanying a dance performances.

Many traditional instruments are used, and it gives the entire play a unique sound.

#11 Wrap-Up

Oh boy was that a long blog post, the longest I’ve ever written so far, totaling over 3.000 words, over 1.000 words longer than all of my other posts . I have my notebook open in front of me now and although I still have notes about other things related to Kabuki, but if you want to learn more, please let me know and I’ll do my best to reply in the comments. This blog post took so long to write, I have 16 tabs open at the moment with research and I have 2 books next to me.

You might notice that I used quite a lot of Ukiyo-e images in this post, if you’d like to learn more about the Japanese woodblock print technique, you can read up on it in my post on the Ukiyo-e Museum in Matsumoto

My trip to the National Theatre in Tokyo to see Kabuki was part of my AFS Tokyo Trip, in which we also visited the Shueisha Publishing company, the company behind Shonen Jump and many more. You can read more about that trip here. We also went to the Studio Ghibli Museum, which will hopefully be my next post, if I forget to link it here, leave a comment and I’ll fix it.

I never really say this because it never felt justifiable, but after spending so many days on this post, go follow me on Instagram and Twitter for updates on all of this, and share it with all of your friends.

Until next time,

send a postcard,

Yona

Sources:

50th Anniversary National Theatre Guidebook

The Kabuki Handbook, written by Aubrey S. and Giovanna M. Halford

factsanddetails.com/

http://www.kabuki-bito.jp/

https://sites.google.com/site/utnarukami/

and quite a few more, oh, and a tiny bit of Wikipedia too.

Great and comprehensive write-upl!

Thank you also for including the video, which does a great job in illustrating the topic.

Norbert

[…] being things like the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka city, or a visit to the National Theater to see a Kabuki performance, and, although you can expect blog posts about both of those things in the following days, this […]

[…] you’ve ever read anything on this blog, you will probably know that I love Kabuki theatre. The next anime about Japanese culture is a show about pretty boys doing pretty […]